Welcome to this lesson on reading and understanding archival diaries.

The lesson outlines a number of steps on how to start deciphering unfamiliar handwriting, where to start contextual research and how to follow leads, and how to transcribe archival diaries.

Kirsten Mulrennan and Rachel Murphy, 'Opening a window to the past: Researching archival diaries', University of Limerick Special Collections and Archives Department website (https://specialcollections.ul.ie/research-diaries/) (Date accessed).

1. Introduction

Practice, practice, practice!

It takes time and patience to easily read a new handwriting style, particularly one that uses words, phrases and formatting that differs from modern handwriting styles. Reading handwriting is a learned skill, and cumulative experience over time definitely helps when approaching any handwritten document. This lesson outlines a number of common words, phrases, abbreviations and ligatures that may appear in personal diaries in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.1

However, it is important to remember that handwriting is unique to each author, so it may take time to familiarise yourself with a certain style. Moreover, even the handwriting of a familiar author can depend on a number of factors, including:

- The time period the diary was written in

- Whether the author meant for the text to be legible to others (i.e. using shorthand or code, or other uncommon abbreviations)

- The type of pen and paper used – for instance, ink from fountain pens can often make letters run into each other and therefore less legible

- The emotional state of the author on a given day – handwriting can be less legible when the author is in a hurry, upset (i.e. tear stains), careless (i.e. spillages, inkblots), and even when they’ve been drinking!

This lesson breaks down a number of different techniques to help you begin to decipher the handwriting and follow any potential leads you uncover using archival diaries in your research. Test your skills using the exercises at the end of this page.

2. What is archival transcription?

There are many reasons to transcribe archival documents. It can take a lot of time to read different forms of handwriting, and by taking your own notes from the document, you are ensuring that you are creating an accurate record of that document to consult at a future date, which you may go on to publish as part of your research, or share with other researchers to make their research journey easier.

There are many different types of transcription. Verbatim transcription aims to transcribe documents precisely as they appear, i.e. replicating the full content of the document, including any spelling mistakes or errors, as well as the exact format of the document. Conversely, edited transcription involves producing a mediated version of the original document, i.e. correcting spelling mistakes or errors, tidying formatting, or even omitting any extraneous elements.

Depending on your research question, it is best for you to transcribe archival documents verbatim while in the reading room – this ensures that you have not omitted any important pieces of information or clues that may be useful to you in the future.

It is important that while undertaking archival transcription, that you simultaneously consider three key elements:

- The content of the record, i.e. what the record is about

- The context of the record, i.e. who wrote it, why and when it was written, why the record is important

- The format of the record, i.e. what the record looks like, how it is laid out, how the text appears, if there are any non-textual elements such as doodles, sketches, maps or arithmetic

DID YOU KNOW?

Archival transcription concerns the textual content of documents: it involves reading and understanding the handwriting in a written document, and transcribing it into a new document, either digitally or by hand, so that the content is easier to read, find and access.

Palaeography, on the other hand, is the study of writing systems themselves, as well as the dating of historic documents by analysing the types of writing used. Common types of writing forms in Irish and English archives and libraries include old Irish script, majuscule and miniscule writing in Latin, and ‘secretary hand’, a form of writing used by the professional classes in the 16th and 17th centuries.

3. Getting started with archival transcription

Using P32, the diary of Henry William Massy, this section outlines the basic steps of archival transcription. See also a sample analysis of two pages from Massy’s diary.

click images below to zoom

1. Open a new Word document or blank sheet of notepaper

Count the lines on the document and number the corresponding lines on your blank page.

2. Identify the different types of formatting used:

- Are the lines easily identified? i.e. do they run straight across the page or are they haphazard? Is there any vertical text, and if so, is any of this written ‘over’ the horizontal text?

- Is the formatting relatively straightforward? i.e. is there a clear start, middle and end to the document? How will you incorporate margin notes, stamps, annotations, doodles etc. into your transcription?

- How many pages are there? Are they consecutive? Are there any missing? If there are missing pages, is there also missing text?

- How will you differentiate notes you make to yourself from the actual text of the document? i.e. if typing your transcription, it is a good idea to use a keyboard character that’s unlikely to be found in the original document, or characters not used in archival transcription, so you can easily identify your own personal notes, i.e. using triangle brackets <like this>. If you’re transcribing by hand, you may have a symbol or other form of shorthand that alerts you to your own notes. This is more important than you think – while you may assume you will easily remember which parts of the transcription are verbatim transcription, and which are your own notes, these can often become less clear over time.

3. Try to read document through once to get a feel for the it – what portion of it can you understand from this initial read-through? Can you get a general idea of what the document is about?

4. Begin to roughly transcribe the document verbatim, or the portion of it you can easily understand:

- Leave space for difficult words or phrases, or mark words you are unsure of in square brackets [?like this]

- Find an ‘anchor’ word or phrase, such as ‘Dear Sir’, where you can easily identify common letters

- Identify if the author changes the way they form letters if they’re in an initial position (at the start of a word), or in the middle or end of a word – this if common with letters such as ‘E’ / ‘e’

- Break down difficult words letter by letter. Leave difficult words and come back to them later – additional context and fresh eyes can really help

- Google complete ‘unknowns’ – this could be a word/phrase/subject-specific terminology you do not know, and may have to come back to later

5. Background research is vital in understanding both the context and content of the document. It can help you to work out unusual or incorrectly-spelled words, and will ultimately help you to better understand the document. For more on where to start with contextual research, click here.

4. Common nineteenth century formatting and abbreviations

The meanings of different types of abbreviations depend greatly on the context of the document, as well as the time period it was written in. A sample of common nineteenth century formatting and abbreviations are outlined below.

Common nineteenth century formatting

- {curly brackets} may span multiple lines of text, i.e.

- Hyphen ‘-‘ / en dash ‘–’ / em dash ‘—’ / double ‘=’

- Sentence case/ ALL CAPS/ all lower case

- underline or double underline

- superscript / subscript

singleordouble strikethrough- use [square brackets] to mark unknown words

- use <triangular brackets> to leave notes for yourself, i.e. <page 2 missing>

Examples of common nineteenth century abbreviations

Ligatures and shorthand:

- & or ‘7’ = and

- &c = etc.

- viz= meaning

Dates:

- Months like Apl. = April, or Decr = December

- prox. = proximo (the next month)

- ult. = ultimo (the previous month)

- inst. = instant (the present month)

Names:

- Jos. or Jo~ = James

- wm = William

Titles and acronyms:

- D.D. = Doctor of Divinity

- D.M.P. = Dublin Metropolitan Police

- Esq. = Esquire

- Gen. = General

- P.P. = Parish Priest

- S.S. = Station Sergeant

- Sergt. or Sgt. = Sergeant

- Supt. = Superintendent

- R.I.C. = Royal Irish Constabulary

- Rt. Hon. or Right Honble. = The Right Honorable

5. Background research: a sample ‘research journey’

Background research

Investigating the context of a record not only helps you to better understand the document, but the additional information you come across may help you to work out previously unknown or hard-to-read words while conducting archival research. For more on the importance of critical thinking while conducting archival research, see related lesson on Archival diary as object: interpretation and critical analysis

It is important to ask yourself the following questions:

- What leads or clues can you find in the document? i.e. names, addresses, names of organisations or businesses, known historical events

- Using these clues, where could you begin to search for additional information? For example:

- If the document mentions a famous person, you could try the Irish Dictionary of National Biography

- A known architect may be findable in the Dictionary of Irish Architects

- Unusual placenames may be recorded on Logainm

- Individual family estates or houses may appear on the Landed Estates Database

- English landowners or peers may be listed on The Peerage

- Unusual or less-well-known Irish surnames may have been recorded in the 1901 or 1911 census

- Try to think of alternative sources of information relating to people, places, events – try local newspapers, online emigration records, prison or court records, registers of births, marriages or deaths… the possibilities for archival research are endless!

DID YOU KNOW?

UL students have access to a variety of genealogical and biographical databases through the Library website. Make sure to log in through the Library homepage, then navigate to Explore Collections > Databases A-Z to find the relevant source, i.e. Ancestry.com, the Irish Newspaper Archive, the Irish Times Newspaper Archives and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Sample research journey using the diary of Henry William Massy

Which Massy? Verification through land ownership records

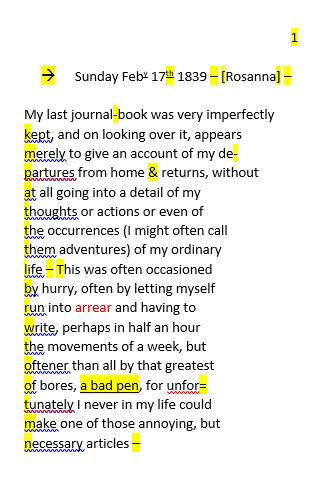

At first, we were unsure of the location mentioned at the top right-hand side of the first page of Massy’s diary. We thought it said ‘Rosanna’, but were unsure. As we knew Massy, the diary’s author, originated in Co Tipperary, a quick check of Google Maps did return a townland ‘Rosanna’ in Tipperary, but we still didn’t know if this was accurate. Further investigation was needed.

Next, we tried the placename database Logainm.ie, but unsually, the townland was not returned here, and nor did it appear as a registered townland during the 1901 or 19011 census.2

Our first breakthrough came from the Landed Estates Database. While there are a number of Massys listed, through a process of elimination, we were able to identify that Massy was associated with ‘Grantstown Hall’, as well as another holding at Rosanna, Co Tipperary. This entry also provided a number of significant further details about Massy:

- a photograph of Grantstown Hall

- the years of his birth and death (1816–1895)

- the name of his grandfather, Reverend William Massy (d 1822)

- that he also held land in the parish of Kilfeakle in the barony of Clanwilliam at the time of Griffith’s Valuation (1848–1864)

- his estate at Donaskeigh, Grantstown and Killoge was advertised for sale in 1866, and was bought by Charles W Massy

- the Massy estate numbered 707 acres in Co Tipperary by 18703

Looking further into the Grantstown Hall estate revealed the name of Massy’s brother, Henry W Massy; the Landed Estates record states that by 1894, the estate was the seat of a General William Massy; that the estate was associated with the Massy family until at least 1906; and that the estate remains extant and occupied today.4

The map and coordinates available through the Landed Estates Database confirm the location of the townland of Rosanna from our initial Google Maps search was correct.

Tracing the extended Massy family

Using these identifying details, it was now possible to trace Massy through a number of different genealogical records. Through IrishGenealogy.ie, we were directed to the National Archives of Ireland Genealogy website, and were able to find Massy’s will, containing his date of death, 20 November 1895, as well as the name of the executor of his will, Anna Massy, Spinster. His will also stated that Massy served as a Major in the Tipperary Artillery. IrishGenealogy.ie also directed our search to the General Registry Office (GRO), where his death certificate revealed that he died as a result of ‘cardiac failure’ at Grantstown. Massy’s death was also recorded in the Dublin Evening Telegraph newspaper, 23 November 1895.

A search on Wikipedia gave us the name of one of Massy’s sons, Lieutenant General William Godfrey Dunham Massy (1838–1906). Another search using the Cambridge Dictionary of Irish Biography built on this, disclosing the name of Massy’s wife to be Maria, while the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography revealed her maiden name to be Cahill.

ThePeerage expanded our knowledge about Massy’s family, outlining: the names of Massy’s parents, Reverend William Massy and Elizabeth Evans; giving the date of his marriage to Maria Cahill as February 1838; stating that he also served as a JP (Justice of the Peace, or Magistrate) for counties Tipperary and Limerick; and the names of his eight children (including one of his daughters Anna Massy, the executor of his will). This material was alternatively available through a search of the English census, which further recorded Massy and his family lived in Kensington, Middlesex, in 1861, and at Lee, Kent, by 1871.

The research journey outlined above demonstrates the investigative nature of archival research, as well as the importance of following any clues within the document, to learn more about the context and content of the material you’re looking at. In this case, our research confirmed the location of where the diary was written, and gave us much-needed contextual information so we could better understand, and therefore decipher the handwriting contained within, the remainder of the diary.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Special Collections and Archives Department at UL do not hold general genealogical records, such as records of births, marriages and deaths. The best places to begin your genealogical research include:

- local, city and county archives and library services (for Munster archives, see our A–Z list of research resources)

- the General Register Office (GRO)

- the Registry of Deeds

- the National Archives of Ireland (for more, read more at the NAI’s genealogy website and see its free genealogical service)

- the National Library of Ireland (for more, see the NLI’s guide to getting started with family history research, its dedicated genealogy service , and its newspaper database)

- irishgenealogy.ie

6. Transcription exercise

The best way to learn archival transcription, is by doing it for yourself! See how many of the below excerpts you can transcribe accurately and fully. Click the questions below each exercise to reveal the correct answer.

Exercise 1

Exercise 2

Exercise 3

7. Quick Quiz

Time's up

8. Further reading and resources

- Lauri Hyers, Diary Methods: Understanding Qualitative Research (Oxford Scholarship Online, 2018) DOI:10.1093/oso/9780190256692.003.0003

- Palaeography: reading old handwriting 1500-1800, The National Archives (TNA), UK

- Digital Recipe Books Project, University of Essex, UK

- Transcription Tips, The National Archives, US

- How to Transcribe, Library of Congress, US

- Reading and Understanding Medieval Documents, University of Nottingham, UK

- How to decipher unfamiliar handwriting: A short information to palaeography, National History Museum, UK

- Palaeography lessons, Staffordshire Archives and Heritage, UK

- Palaeography Guides, Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, UK

- Reading the Past: Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century English Handwriting, Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, UK

- Transcribing Europeana 1914-1918

- Europeana Transcribe Transcribathon, as well as ‘Tips for Transcribing‘

- Queen Victoria’s Journals, Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the Royal Archives, UK (paid portal, free trial available)

- In handwriting, a ligature occurs when two or more letters are joined together in a single symbol, i.e. ‘et’, Latin for ‘and’, is commonly shortened to the ampersand symbol ‘&’.[↩]

- While the time period of the diary and the Irish census online differ significantly, the census is nonetheless invaluable when checking the spelling of unusual Irish names or locations.[↩]

- Source: Landed Estates Database, ‘Estate: Massy (Grantstown)’.[↩]

- Source: Landed Estates Database, ‘House: Grantstown Hall’.[↩]

You must be logged in to post a comment.