Welcome to this beginner’s guide to archival research

This page addresses the most commonly asked questions about where to start your archival research. It is divided into six sections: an introduction to special collections and archives; the rare book and archive collections held at UL; getting started with archival research; how to access special collections and archives at UL; getting started with critical thinking and analysis; and recommended further reading and resources.

click on each question below to expand the answer

Kirsten Mulrennan and Rachel Murphy, 'Opening a window to the past: Researching archival diaries', University of Limerick Special Collections and Archives Department website (https://specialcollections.ul.ie/research-diaries/) (Date accessed).

1. Introduction to Special Collections and Archives

How are ‘special collections’ and ‘archives’ different from the main library collections?

The Glucksman Library’s ‘unique and distinctive collections’ are held apart from its main collections, and are made up of archives, rare books and journals. These collections follow a number of research themes, and include items that are of local, national and internal interest. The collections support teaching and learning at UL in a number of ways – students come and access the material generally as part of their coursework, or they can undertake a more focused study for FYPs, MAs, PhDs and beyond. We also support external researchers and academics.

Our material dates from around 400AD to present – that’s almost 2,000 years of history, contained in over 2,000 boxes of archival material and 40,000 printed works.

What are primary and secondary sources?

Our collections include both primary and secondary sources.

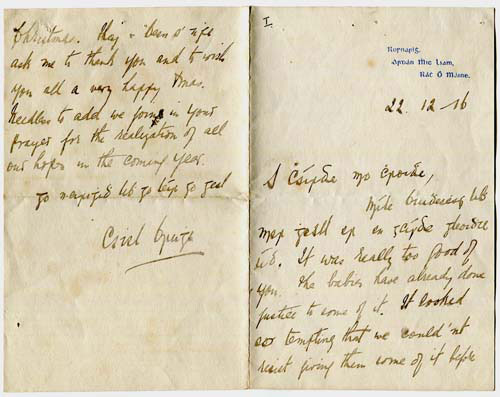

Primary sources are created in the moment, as the result of an activity, or by a witness to an event. These documents are the ‘stuff of history’, they provide evidence of past people, events and institutions. They include a range of material – for example, manuscripts, letters, maps, diaries, photographs etc.

In contrast then, secondary sources are created after the fact, and they’re based on the accounts held either in primary sources, or in other secondary sources. This means that these sources represent an interpretation or an analysis of an original source, and examples of these include printed works, textbooks, reference books and bibliographies.

For more on using primary and secondary sources in historical research, see related lesson here.

What are archives?

Archival collections are made up of unpublished material that cannot be found anywhere else. Archives contain primary sources – original and unique source material that provides evidence of past events and the activities of past people and institutions.

Archives can be textual, so they can be handwritten or typed, and they can be non-textual, and this includes everything from photographs, maps, audiovisual material, as well as objects – we actually hold a cannonball from the First World War in our Armstrong collection. We have to include a warning on the box to say how heavy it is!

Where do archives come from?

Archive collections come to us from a variety of different sources: they can be made up of papers from local families or estates, records of local businesses, political parties or societies, the personal papers of authors and poets, and so on. These previously ‘unseen’ collections can incorporate anything from medieval manuscripts and maps, to nineteenth century photographs and letters, to VHS tapes from the 80s, and everything in between.

There are a number of different archives services, and these not only include dedicated national, county and university archives, but the archives of businesses and religious institutions, as well as hospitals and military institutions. If there’s a topic you’re interested in, it’s always worth getting in touch with an organisation to see if they have an archive, or if their records have been donated to a dedicated archival institution.

What happens to archives before a researcher sees them?

At a basic level, archivists collect, manage and provide access to primary sources. Archivists also encourage use of this material – they facilitate and enable research and help their users build archival literacy, which means that they’re building the skills that they need to be able to search, find, access and critically analyse archival material for themselves.

There are lots of different interconnected stages in the archival process — the following is a very brief outline of the types of work an archivist does when dealing with archival collections.

Appraisal

Archival collections come to the archive in a variety of ways. Usually, collections are donated to the archive by a donor, either the creator of the records, or their next of kin.

‘Appraisal’ is the term used to describe the process of how an archivist assesses an item, or a collection of items, to determine its ‘archival value’ — in other words, how rare or significant the items are, and if they will be of interest to current or future researchers. It isn’t possible, or desirable, to keep everything from the past, so an archivist’s professional experience helps them assess and recommend items for archival preservation, return to the donor, or in certain circumstances, destruction.

An archivist starts by researching the context of the collection to better understand who created these records and why, and what the records add to the narrative we already know about a certain period, event or person — if we’re very lucky, they may even tell us something entirely new about the past.

Arrangement and description

Archivists arrange and catalogue archival records to make them easily findable.

‘Provenance’ is the term used to describe the process of how an archivist, based on their research about the collection, its donor and its history, begins to reestablish, insomuch as is possible, the ‘original order’ of the items, so that they reflect the way they were originally created. Provenance allows archivists to arrange records into categories or ‘series’, so that the context of the records is not lost — arranging records as close to their original order as can be established allows the records to speak for themselves, so that they can be later analysed by researchers. For example, arranging a series of correspondence by author or recipient is much more reflective of the organic context of each letter’s creation, than if all letters in a collection were arranged according to topic.

Once the archivist is happy with the arrangement of the collection, they begin to catalogue or ‘describe’ the records.

Archival catalogues have a number of significant differences to the main library catalogue, which uses the Dewey Decimal classification system. This system assigns each volume a decimal number from 000—900 based on its subject matter, author, title and year of publication.

In contrast, archival description is ‘hierarchical’. The codes assigned are usually alphanumerical and reflect the system of arrangement of the collection. This hierarchical approach to cataloguing allows the archivist to capture the complexity of the collection while minimising repetition in their descriptions. More importantly, hierarchical description allows users to search and browse archival collections by context as well as via keywords. The overall collection is described first — who created the records, when they were created, why they are important, how they came to the archive etc. This means that this information does not need to be replicated for each record within the collection. The archivist then moves on the describe the next ‘level’ of the collection, i.e. the series, files and individual items. Archival cataloguing is a very subjective process, and while the general principles are the same, the arrangement and description of each collection will vary according to its extent and its contents.

Archivists all over the world use the same standard for archival description, which is laid out by the International Council on Archives (ICA). Read more about the General International Standard for Archival Description (2000), commonly known as ISAD(G), here, or a brief summary of its most important elements which will help you with understanding and citing archival material.

For more information on reading and understanding archival catalogues and numbering systems, see Section 4: Getting Started with Archival Research below.

Preservation

In addition to establishing intellectual control over collections, the archivist must also oversee the physical preservation of the material in their care.

On first receiving a collection, the archivist removes all metal paperclips, staples and pins, as well as rubber bands and sellotape (where it can be easily removed). These are replaced with special plastic paperclips to keep items together. ‘Smokesponges‘ and brushes are used to remove surface dirt from material.

The archivist writes a reference number on each document in 2B pencil, as this is much easier to erase and does not imprint the document as much as a regular HB pencil. Documents are unfolded or unrolled where possible. Material is then packed into acid-free folders, and placed in acid-free boxes. Photographs and particularly fragile textual documents are protected further using sheets or pockets made from a clear polyester called Mylar.

The boxes are then stored in light, temperature and humidity controlled ‘strongrooms’. These rooms are equipped with water alarms to alert staff to the presence of water, whether through a leak or a flood, as well as fire suppression systems. Staff keep a close watch on the environmental controls and alarms in these storerooms to ensure the conditions remain within the acceptable range laid out by international standards, especially during extreme weather events, such as a heatwave.

To ensure the continued preservation of this unique material, we ask our users to take similar care when consulting archives in the reading room – handling procedures must be adhered to, no liquids or pens are allowed near the documents, only pencils, and you must be careful not to lean or press on the documents.

For more information on handling fragile documents and the reading room rules at UL, see Section 3: How to access Special Collections and Archives at UL and Section 4: Getting Started with Archival Research below.

Conservation

As well as the ongoing long-term care of archival material, archives also undertake more concentrated active care of damaged or fragile material, and this is what’s known as ‘conservation’. This aims to prolong the life and accessibility of the collection. If material comes to us badly damaged by water or fire or mould or insects or tearing, a professional conservator will intervene. Some of these interventions can be quite small, for instance repairing tears in the paper and flattening really tightly folded material, while other repairs are larger, such as rebinding material. This is a delicate process, and takes place in a dedicated conservation lab.

Digitisation

In order to both increase access and aid preservation, archivists digitise material. Digitisation is the transfer of analogue or physical material into a digital form. This includes scanning or photographing material to enable online sharing, publication or even a closer analysis of a document’s handwriting.

However, digitisation is not the same thing as digital preservation. Once you scan the original, you now have to preserve two items – the original which is kept in the strongroom as usual, but now also a digital copy, which can sometimes be more vulnerable than the original itself. For instance, a jpeg image will degrade over time the more you access, edit, copy and send it through email etc. So digitisation is not the same thing as digital preservation, digitisation necessitates digital preservation. This one of the reasons why we can’t digitise everything, and why archives usually only digitise a small selection of material from a collection.

For more information on the different steps and considerations in digitising material, please see the ‘Digital Foundations’ LibGuide here.

Access

Access to material is provided in a number of ways. In the first instance, researchers can make an appointment to view the material in our reading room.

Read more about our reading room opening hours and reading room rules. Email specoll@ul.ie to make an appointment. Please note that due to current Government guidelines, our reading room is closed to the public until further notice.

Archivists are guided by legal, professional and ethical standards. This means that we cannot always provide access to material if it is closed under Data Protection legislation like GDPR, or if it contains any ethically sensitive information. However, the reason(s) for a record’s closure will always be declared in the archival catalogue.

Where possible, we also provide digital access to our collections to enable remote access. Low resolution digital copies of items will be provided to students on request for private research and study – we just need a signature from you to declare that you won’t publish or share the images without permission. We can also arrange high resolution scans for selected items if required for publication. Please note digital copies of material may not always be possible due to the condition and binding of some material, as well as copyright and GDPR considerations. Email us at specoll@ul.ie to enquire further. Information on the charges for this service can be found here.

Outreach

Ultimately, as the professionals who know the material best, it is the archivists’ job to tell the wider world what amazing resources we have, so that everyone can access and appreciate them, whether that’s looking at a small selection of material through a physical or online exhibition, or a more in-depth study as part of coursework or in preparation for publication.

‘Outreach’ is the term used to describe the process of how an archivist actively seeks to engage the users of archival collections. Archivists undertake outreach in a variety of ways — curating exhibitions, hosting seminars and workshops, publishing, creating pamphlets or brochures, writing blogs, or keeping active on social media.

Why aren’t all archival collections digitised?

The US National Archives defines digitisation as ‘not just as the act of scanning an analog document into digital form, but as a series of activities that result in a digital copy being made available to end users’. Roughly one-third of any digitisation project is made of physically scanning material – the rest involves careful project and budgetary planning, considering the best file formats for access and long-term preservation, using the correct hardware and software, applying appropriate metadata standards and policies, image editing and quality control, as well as assembling digital exhibitions or portals, in conjunction with contextual text and narrative. The availability of staff, resources and technology also impact the feasibility and long-term sustainability of digitisation planning, as well as copyright considerations.

Overall, the Northeast Document Conservation Centre (NDCC) in the US argues that the selection of material for digitisation depends on three key considerations:

- Should it be digitised? What is the value of the content of a collection or portion of a collection? Remember: not all archive collections warrant digitisation.

- May it be digitised? Including copyright, intellectual property rights and even Data Protection legislation.

- Can it be digitised? Including practical and technical aspects of the project, including available staff and budget.

For more on the various steps in digitisation, see the Glucksman Library’s Digital Foundations LibGuide, the Digital Repository of Ireland (DRI), as well as the US Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initative.

2. ‘Unique and distinctive’ collections at UL

What archive collections are held at the Special Collections and Archives Department?

We currently hold over 200 archival collections, and the catalogues for over 30 of these are available online through the library website for you to search. These cover a broad variety of topics, from architecture and business, to estate and family history, Irish military history and rebellion, as well as the personal papers of a number of literary figures, including Limerick author Kate O’Brien.

We also hold the National Dance Archive of Ireland (NDAI), and this consists of collections from over 70 dance companies in Ireland, covering Irish dance and ballet, to contemporary dance, and even Flamenco.

click here to access A–Z list of archival catalogues, or browse the different types and research themes of our archival collections

What rare book collections are held at the Special Collections and Archives Department?

Our printed collections include rare, limited or first editions of books, locally printed journals and other rare printed material. Some of our collections also feature a number of ‘incunabla‘, which are books printed before 1501.

These collections are usually thematic, and reflect the research strengths of the University, and the interests of individual faculties and academics. For example, we recently acquired a collection of Gothic literature for a faculty member in the English Department, who uses the collection in a second year module.

- The Norton and Leonard collections contain thousands of volumes of local and national interest, as well as a variety of associated archival material, including over 12,000 postcards from counties all over Ireland, manuscripts, prints, maps and other rare items.

- The Bolton Library consists of over 12,000 early printed texts and inunabla, and cover a variety of topics, from science and medicine, to religion and languages. So far, about one third of the material has been catalogued and over 50 items have been discovered that are completely unique to the collection and do not survive anywhere else in the world.

- The McAnally Travel Literature collection includes travel guides and accounts from all over Ireland and abroad, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

- The Gilsenan Yeats collection contains a number of first and rare editions of the works of WB Yeats.

- The Ó Súilleabháin Irish language collection, donated to the Glucksman Library in 2016, contains Irish language published texts and other materials relating to the subjects of Irish literature and culture. The material ranges in date from the early eighteenth century to the late twentieth century, and is currently being catalogued.

- Work is also underway to catalogue the Eoin O’Brien Collection, a large volume of books which cover Irish and International art, artists, art history and art collections

3. How to access special collections and archives at UL

How do I access the department?

Opening hours and location

The department is open 9–1 and 2–5 Monday to Friday, and is located in GL0-051, on the ground floor of the new wing of the Glucksman Library, beside the Grand Reading Room and the ARC viewing window. Entering the library through the security gates, turn left and walk to the end of the corridor – the department is on your right after the staircase.

Please note that due to current government restrictions, the reading room remains closed to visitors, but department staff are operating a remote service where possible via phone 00353 61 202690 and email specoll@ul.ie.

Department staff

Our department team is diverse, and is made up of librarians, archivists and a conservator. Each staff member has their own field of expertise, so when you email specoll@ul.ie with your query, you will be directed to the best person to help you.

Services

At the moment, due to current COVID restrictions, we are operating a remote enquiry service. We also offer online research consultations on a one-to-one basis, and we run a number of classes, workshops and Q&A sessions, both online and onsite.

Online presence

The department has an active online presence. For the most up to date information about the department, subscribe to our Unique and Distinctive blog, and follow on social media @UL_SpecColl.

What are the reading room rules and why are they important?

We protect the material in our care to the highest international standards. As outlined above in relation to preservation, we do this in a number of ways, by keeping material stored in secure and monitored strongrooms, and by using acid-free folders and non-metal paperclips.

However, the preservation of ‘unique and distinctive collections’ does not stop at the door of the strongroom — it continues into every interaction staff and users have with an archival record or a rare book. These simple measures help us to preserve the document as it is, without additional damage, for future generations.

An explanation of the reasons behind our reading room rules is outlined below:

- Readers must sign-in on entry, and photographic identification (student card, passport etc.) must be provided. We do this for a number of reasons. We gather anonymous user statistics, so we can better understand and provide tailored services to the many different types of users who access our department, whether faculty, students, external researchers or members of the public. This is also a security and preservation measure — we keep track of which items have been consulted by each user, to prevent damage or theft.

- Coats, bags and other belongings cannot be brought into the reading room. Lockers are provided in reception. This is another security and preservation measure — by limiting the number of belongings each user can bring with them into the reading room, staff can more easily keep an eye on correct handling procedures, as well as ensure that all items issued are returned at the end of each user’s visit.

- Items must be handled with great care at all times and must not be marked in any way. Please ask a member of staff if unsure of correct handling procedures. For more on handling fragile documents, see Section 4: Getting started with archival research below.

- Only 2B pencils may be used for note taking. These are available at the reception desk. The rationale for using 2B pencils in the reading room is outlined above — accidental marks made by this type of pencil is easier to remove than those made by a HB pencil. The use of pens or tippex is understandably forbidden! Users can also opt to take their laptop into the reading room, should they wish to take notes electronically.

- Phones and laptops must in on ‘silent’ mode. Headphones must not be loud enough to disturb other users. This is common courtesy for users and staff.

- Food and drink are not permitted in the reading room. No matter how careful we are, spillages are inevitable, and even water can have dire and irreversible effects on an already fragile document. For this reason, absolutely no food or drink can be brought into the reading room — this includes water, as well as throat lozenges or chewing gum. Users are welcome to step out into the reception area as frequently as they like to take a drink of water. There is a café located on the ground floor of the library for users who wish to consult material over a longer period.

- Requests for photocopying and/or use of digital camera must be made to department staff. You will be required to complete a copyright declaration form before making copies of any records. This is an important measure to prevent unlawful copying or sharing of unpublished material. It is also another preservation measure — some material is too fragile to be photocopied and may need be carefully photographed instead, if at all. You can also request library staff to make copies for you. For more information on the charges for this service, click here.

- Items held in Special Collections and Archives are for reference only and may not be taken outside the reading room. Items can be held behind reception for researchers who wish to consult material over a number of days. It goes without saying that all the steps staff and users take to carefully preserve material would be negated by the removal of the material from the protected environment of the reading room. While some of our material is quite recent and robust, it still must be carefully handled and preserved if it is to remain so for future generations.

Are any of UL’s archival collections online?

The Glucksman Library will soon launch its new Digital Library, where digitised collections, or portions of collections, will be made available over the coming months. Watch this space!

The department also hosts a number of online exhibitions which can be accessed through the ‘exhibitions’ tab on the main menu. Current exhibitions include:

For links to other archives services and resources online, read through our A-Z list here.

What if UL doesn’t hold the archival collection I’m looking for?

As archival collections are rare or unique, they are usually held only in one institution, while multiple parts of a collection can be spread across multiple institutions. As archival institutions cannot take in every archival collection due to space and resource constraints, archival institutions generally have ‘collection policies’ – guidelines which outline the types of archival material they take in, for instance, in relation to particular research themes. For example, the Special Collections and Archives Department at UL generally only accepts archival material which relates to Limerick city and county, and which relates to the research strengths of the university’s faculty, so that students have the necessary material available to them when undertaking a particular module.

Furthermore, as the context or provenance of archives collections is paramount, institutions will not take in collections that are more appropriate for other archives services, unless there is no where else for them to go. For instance, the National Archives would generally not take in records relating to a Clare business, as these would be more appropriately held in the Clare County Archives. Likewise, the archival records of a government department would never be donated to a local archive, as these fall under the remit of the National Archives.

In this way, archival institutions work together to preserve the records of our past, and to hold records in the most appropriate institution as possible, so that locally-created records are more readily accessible by the people in that locality. There are some exceptions to this, i.e. for collections of national importance, or those purchased at auction. As a general rule, it is always worth thinking about where you think the collection you’re interested in is most likely to have ended up, and begin your research from there.

This is why undertaking some initial research before an archival visit is so important – where are the records most likely to be kept? This is the best place to start!

How do I find other archival collections that are relevant to me?

Knowing where to start is often the most difficult part of locating special archival collections, especially if you’re unsure if they have survived in the first instance.

- As mentioned above, it is important to consider the types of collections held in any particular institution. What patterns do you see? What research themes are strongest? This is usually evident in the archives’ ‘mission statement’, which outlines the type, date, and topic of material they tend to collect.

- Remember that there are a number of different types of archives services –not only includes dedicated national, county and university archives, but also the archives of businesses, hospitals and religious institutions. If there’s a topic you’re interested in, it’s always worth getting in touch with an organisation to see if they have an archive, or if their records have been donated to a dedicated archival institution.

- When in doubt, google it out! Often, as broad a keyword search as possible may pick up mention of an archive or surviving documents from a collection, whether from an archive catalogue, a publication, or even from a blog post written by an academic who has used the material in the past. For this reason, it is always worth tracing the footnotes and references of any academics who have published in your area, as they may refer to sources of which you were previously unaware.

- There are a number of useful ‘archival portal’ websites online, which aim to bring the catalogues and/or contact details of various archival institutions together in once place, to make searching easier. In Ireland, browse the Irish Archives Resource (IAR), while the UK National Archives’ (TNA) Discovery catalogue searches record entries from a selection of 2,500 archives services in the UK, Ireland and abroad.

- Follow any and all leads! Keep an eye on press releases, newspaper articles or research projects announcing the donation or work on a particular collection. Follow a range of archives institutions on social media and through their blog posts, for the latest news.

- Make contact. Send an enquiry to an archive institution with similar collections, to ask if they know the current whereabouts of the material you’re looking for. Likewise, contact relevant academics in the area, as they may be aware of, or have worked on, similar material in the past.

4. Getting started with archival research

How do I search special collections and archives at UL?

Printed collections

Our printed collections are available to search using the main Glucksman Library website. Filter your research using to dropdown menu to ‘special collections’. If you wish to search the Bolton Library in particular, you should use the search term ‘Cashel Diocesan Archive’ and that will narrow your search to all items catalogued to date from that collection. For screenshots of this process, click here.

More information on each of our rare book collections is available here, under the ‘rare books’ tab.

Archive collections

An archival catalogue is created for each archival collection we hold. Currently, these must be searched separately from the main library catalogue, and are available to download.

For more information on each of our archive collections, and to download each catalogue, click here, and select the ‘archives’ and ‘National Dance Archive of Ireland (NDAI)’ tabs.

Browsing collections

If you’re not looking for anything in particular and you just want to browse our collections, you can do so in two ways:

- To browse collections by type, i.e. rare books, archives or dance archives, click here.

- To browse collections by research theme, click here.

As the volumes in the Bolton Library are so diverse, there are too many research themes to list in their entirety. To browse sample research themes in the Bolton Library, click here. If you have any questions about particular topics in the Bolton Library collection, please email specoll@ul.ie, and our Bolton cataloguer will get back to you with more specific research advice.

What should I consider before I make a visit the archive?

Practicalities of archival research

Archival research is time-consuming. In order to make the most out of your visit to the archive, or to better inform your emailed research enquiry, it is vital that you do some research into your topic, and the department’s holdings, before you come to visit us. Important questions to ask yourself are:

- Does UL hold the collection I’m looking for? Be sure to search through our collections to make sure we hold the material that is relevant to you. Read more here about what to do if UL doesn’t hold archival material relevant to your particular research question.

PRO TIP: read the catalogue! The archival catalogue is the first and best source of information on any collection. It is important that you read this carefully, both in terms of the context of the collection at the beginning, and in terms of the detail on individual records within the collection. For more on how to read an archival catalogue, click here.

It is also helpful to do a general search on the Glucksman Library website to see if there are any related secondary sources on your topic, as well as our blog and twitter account, to see if we have recently shared any material which may be of interest. - What is my research question? The more specific you can be about what you’re looking for, the easier you will identify a ‘starting point’ for your research – this is especially important when beginning to tackle a large collection. Specific research questions will also make it easier for department staff to help you, by advising on our holdings in relation to that topic, and/or suggesting where you might begin your search, either within UL or in another institution.

- Have I done enough background research? Depending on your research topic, there may be many initial research avenues open to you. If you’ve done a thorough online search, searched the library catalogue and read the archival catalogue, have you also had a look through any relevant printed bibliographies and other research resources? Have you had a look through the footnotes and references of related articles and books, to see what other academics and students in your field have found (or not found)? Have you asked the staff at the archive for some additional advice?

- Are there any possible sources on my topic that may not be immediately apparent? It is best to consider your research question from all angles. Archival collections are diverse and complex, and sometimes may contain material relating to a variety of different topics at once. For instance, at UL, we hold the papers of Kate O’Brien, a celebrated Limerick author. While this collection contains manuscripts and drafts of her work, much of her surviving outgoing correspondence is actually captured in the Stephen O’Mara collection, former Mayor of Limerick and Kate’s brother-in-law, with whom she had a very good relationship. It never hurts to follow all leads – sometimes, a key document can turn up in the most unlikely of places! Try broad keyword searches also, to make sure you’ve cast your net as widely as possible.

- How much time do I have? Archival research is a process, and it takes time to find, access, search through, analyse and write up the information you come across in an archive. To avoid disappointment, it is best to give department staff as much notice as possible about your visit or request, and to give yourself as much time as possible to complete assignments.

Time management

Following on from the last point above, if it is your first time visiting an archive, or if you haven’t been back in a while, it can be hard to anticipate the logistics of the reading room, which need to be built into your time management:

- As mentioned above, it is vital that you familiarise yourself with our holdings and read any relevant catalogue(s) before coming in, so you know where to start. Searching through the catalogue to find items of interest can be time-consuming, so do this well in advance so you can maximise your time on-site with the records.

- Once you have identified the relevant material, you will need to complete a document request form and submit this to the reading room staff who will retrieve it for you. We have over six strongrooms located all around the Glucksman Library, so retrieval may take a little while – to speed this up, it is useful to email us at specoll@ul.ie to request documents in advance.

- Once staff have retrieved the archival material for you, they will issue this to you in batches, not all at once. We do this so we can keep track of what has been issued to which researcher. You will need to return any items you’ve already consulted to the reading room desk, before another batch of material is issued to you.

- Correctly handling archival material takes time. Pages must be carefully turned, items cannot be quickly ‘flicked through’ and must be carefully replaced in their respective folders, in the order in which they were presented to you.

- Reading and understanding archival documents takes time. This process is a vital part of the research process, and cannot be rushed. It takes time to familiarise yourself with different handwriting styles. For more on reading and transcribing handwriting, see our lesson on archival transcription here.

- Note-taking is time consuming. As outlined in relation to citation, it is important that you keep an accurate record of the items you’ve looked at, including items of particular relevance, or items you may wish to consult again at a later stage. This means keeping track of the item’s unique reference number, as well as other key points about the document. If copies or photographs of the material is not possible, you will have to transcribe the document, or portions of it, for your own notes. For more on citation, click here. For more on understanding archival numbering, click here.

- As you cannot eat or drink in the reading room, you must schedule breaks into your research day. Archival material must be handed back to the reading room reception before you leave, and the staff can keep this material safe for you when you get back. Please also note that the reading room closes for lunch 1–2pm.

- You must leave your belongings in the reading room lockers, and only take necessary equipment into the reading room with you. This includes laptops, notebooks and pencils (not pens). Make sure you’re well prepared for your archive visit.

Most importantly, don’t panic!

We have a range of research guides available online, and our department staff are always here to help if you need some guidance. Archival research can be daunting at first, but once you’ve got the hang of it, it will come naturally, and you may even enjoy the hunt for the perfect resource!

How do I understand archival description and numbering?

What is ‘metadata’?

‘Metadata’ is ‘data about data’, or ‘information about information’. It is a way of recording similar types or ‘elements’ of information about different objects in a standardised and structured way, so that researchers (and machines) can read and understand them. Metadata describes the content as well as the physical attributes of an object. For example, the metadata about an archival photograph will describe what the photograph is about, as well as its dimensions, the date it was taken, its ‘medium’, i.e. whether it’s digital, a glass plate negative, a black and white negative etc., what collection it belongs to, and where it is stored.

Metadata is vital for archival description – without proper metadata, material may be irretrievable (because you don’t know where to look for it), unidentifiable (because you have no record of the context of the object), and unusable (because you can’t verify any key elements of information about it). Therefore, metadata is vital for the correct identification, management, access, use and preservation of archival material.

There are over 150 different types of metadata standards for recording and organising cultural heritage material. The International Standard for Archival Description or ISAD(G) is one metadata standard used in describing archives. While you don’t need to know this standard in great detail, it helps to understand the basis of ISAD(G), so that you better understand the archival catalogue.

Understanding archival description and ISAD(G)

Archival description uses metadata to capture the content, structure and context of items. This means that items are always described in relation other items in a ‘fonds’ (or ‘collection’) – a group of documents that share the same origin and that have occurred naturally as an outgrowth of the daily workings of an agency, individual, or organization.1

In order to demonstrate relationships and contents between all items in a collection, archival description is hierarchical. This means that:

- Description proceeds from general to the specific, i.e. the overall collection is described first, then the description is broken down by series of files, then by the contents of files and items.

- Information should be relevant to level of description, i.e. the biographical detail of the creator of a collection is more appropriate at ‘collection’ level rather than ‘file’ or ‘item’ level.

- Descriptions should be linked between levels – making clear the unit of description demonstrates hierarchy and context, and shows more clearly how items relate to each other, i.e. this ‘item’ belongs in this ‘file’ which belongs in this ‘series’ which is part of this overall ‘collection’.

- No information is repeated unnecessarily, i.e. biographical details outlined at collection level do not need to be repeated for each record described.

For more on ISAD(G), see the International Council on Archives website, and the ISAD(G) guidlines.

While each archive has its own method of cataloguing and ways of presenting their archival catalogues, ISAD(G) requires 6 essential elements of description to be included at all levels of description. These are:

- Reference number, i.e. a unique identifier for each collection, series, file and item, assigned by the archivist. This is usually marked in pencil on the top right-hand corner of the document.

- Title, i.e. brief description of what the item is.

- Creator, i.e. who created the record.

- Date(s), i.e. the date an item was created, or a date range which a collection covers.

- Extent, i.e. how many pages in an item, how many files in a series, how many boxes in a collection.

- Level of description, i.e. if the description relates to an individual item, a file of items, a series of files, or an overall collection.

As mentioned above in relation to citation, the first 4 of these 6 essential elements are the most important for researchers to note for their records, so they can accurately reference archival material, as well as keep track of the items and collections they have looked at.

Archival numbering

Archivists use alphanumerical codes to give each archival collection, series, file and/or item a unique identifier. This number reflects the hierarchical structure of the collection, so that the context of the item is always immediately apparent. Each level of description is separated by a dash.

Example:

The Noonan Papers at UL is assigned the collection level code P42. Each series, file and item within this collection reflects the structure of this collection. The examples below are taken from the Noonan Papers:

| P42 | Collection level | Noonan Papers | This number represents the whole collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| P42/1 | Series level | Noonan’s family background | This number represents one series within the collection, relating to Noonan’s family |

| P42/1/1 | Item level | Noonan family photograph | This number represents one item, a photograph, within the series relating to Noonan’s family |

| P42 | Collection level | Noonan Papers | This number represents the whole collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| P42/2 | Series level | Noonan’s military service | This number represents one series within the collection, relating to Noonan’s time in the military |

| P42/2/1 | File level | Noonan’s letters to his mother and father | This number represents one file within the second series the overall collection, contains letter from Noonan to his mother and father |

| P42/2/2/1 | Item level | Letter from Australia | This number represents one item within a file in the second series in the overall collection, this item is a letter from Noonan in Australia, to his mother and father |

How do I read an archival catalogue?

Reading an archival catalogue: collection level

While it’s tempting to get eagerly stuck in to archival research, it really is worth taking the time at the beginning to familiarise yourself with the layout of the catalogue. Depending on the nature of the collection, some catalogues include content tables, family trees, appendices and bibliographies – keep an eye out for any clues or leads that may save you additional but unnecessary research in the future.

Like reading an instruction manual before undertaking a DIY project, much heartache can be avoided by reading about the context of the collection before you begin your research. This is usually included in the identity statement section of a collection’s overall description. This is where the archivist will record any and all available relevant information about the collection and its creators – remember that description is always hierarchical! Always consult the identity statement, for important information such as:

- Name of creator(s), i.e. the people and institutions involved in creating the records

- Biographical history of the creator(s), i.e. key dates, familial relationships, place of birth, career details…

- Immediate source of acquisition, i.e. where the records came from, who donated them to the archive

- Archival history, i.e. where the archives were kept prior to donation to an archive (if known)

- Content and structure, i.e. a summary of what the overall collection is about, highlight key series, files or items

- Appraisal, destruction and scheduling information, i.e. have any records been routinely destroyed since coming to the archive (if determined to be of no archival or research value)

- System of arrangement, i.e. an explanation of how the collection is organised, what each series relates to

- Conditions governing access, i.e. if any records are closed under legislation such as GDPR

- Conditions governing reproduction, i.e. if particular records cannot be copied due to copyright concerns. Always ask a member of staff before taking images of archival material.

- Language/scripts of material, i.e. if the collection is mostly in English, or if it contains items written in different languages

- Physical characteristics and technical requirements, i.e. if a tape-player is needed to listen to audiovisual material

- Related units of description, i.e. if other parts of this collection, or related collections, are held in other institutions, and if so, where

- Publication note, i.e. if records from this collection have been published or referenced in other published works

This list demonstrates the importance of reading the identity statement carefully before you begin, as it is the best source of information for a researcher as to whether the collection is relevant to them, and where to start their research.

Reading an archival catalogue: series, item and file level

While the 6 essential elements above record the context of a record, they do not describe its content. This detail is recorded in the scope and content section for each series, file or item. However, it is important to remember that the nature of material will dictate whether an archivist describes items at series, file or item level, i.e. if a file contains three letters, the archivist may choose to describe the overall file, summarising the contents of the letters, or they may choose to describe each letter individually at item level.

At series, file and item level, the scope and content section is an area of free text, where the archivist can record as much or as little as necessary to accurately describe what the record is about, and to highlight important features of the record. This is obviously one of the most important places to look for a summary of what the series, file or item you wish to consult.

Reading a summary of a document before you consult the original can help you to know what to look out for and to decipher difficult handwriting. It can also greatly speed up and enhance the research process. In many cases, the archivist has already done the hard work of figuring out what the document is about – take advantage of their expertise!

What department forms and policies should I be aware of before I make a visit the archive?

Reading room sign-in

Before your entry to the reading room, you will be asked to complete a researcher sign-in form. We keep your contact details on file, and may get in touch with you regarding material you have requested in the past, or may be interested in in the future. We also gather anonymous statistics about our users, for instance, relating to academic programmes and research interests, so we can use this data to plan and tailor our service to particular user groups.

Copies for personal research use

Low resolution digital copies of items can be provided in certain circumstances to researchers on request for private research and study. Before photocopies or digital copies are issued to researchers, we ask you to sign a form for our records, undertaking not to publish or share the images without permission. Always ask a member of reading room staff before taking photographs in the reading room, and they will be happy to advise you. In certain circumstances, we also provide scans or copies of selected material to remote users via email – please email specoll@ul.ie to enquire. For more information on the charges associated with this service, click here.

Please note that copies may not be possible, when relating to fragile material, or material under copyright restrictions. In certain circumstances, donor permission must be sought before copies can be issued – a member of staff will advise you on this, but please keep in mind a possible delay in response time while permission is sought.

Requesting scans and images for publication, exhibition, broadcast or public display

We can also arrange high resolution scans for selected items if required for publication and display purposes. Similar to the process for requesting personal copies, this process requires the researcher to sign a form outlining how the material will be used, undertaking to accredit the Glucksman Library for the material, and declaring that the material will not be shared with anyone else, or used for any other purpose, without further permission from the archive. For more information on the charges associated with this service, click here.

How do I handle archival and other fragile material?

It is important to remember that every time an archival record or rare book is requested, it must be handled by a staff member, who retrieves and replaces it, as well as by the user who wishes to consult it. For this reason, it is vital that users read and understand the department’s reading room rules, so they understand what is required of them, and know when to ask a member of staff for guidance.

In order to ensure the long-term preservation of such fragile material, it is understandable that department staff must closely control the handling and use of the fragile material in its care. This section outlines the correct procedure when handling archives, rare books and other fragile material:

- Wash your hands before coming into the reading room. Avoid using hand cream or other lotions — this makes your hands greasy and will stain the documents. It is also important to be careful when wearing nail polish that it does not accidentally transfer on to any document you handle.

- Do not use your finger to follow the text on a document. Fingers, regardless of cleanliness, can smudge or smear ink and pencil, and leave marks on porous material such as parchment. You can request an acid-free paper bookmark from staff if necessary.

- Turn pages carefully. Turning pages too quickly or roughly can cause tears.

- Do not lick fingers to turn pages! You’d be surprised how many people do this, forgetting that they’re handling fragile material. Obviously, this practice is not good for the documents. It’s not good for you either — archives are often rescued from a variety of undesirable locations, and while they may look clean, over their long and colourful history they may have come into contact with damp, mould, insects, bird or rodent droppings… not counting the countless of pairs of hands that have handled the document before you!

- When consulting several archival items at once, it is vital that you keep these in the order they are presented to you. The order of the documents has been assigned by the archivist. Each item is given a unique reference number, usually located on the top-right hand corner of the document.

- Do not mark, fold or crease documents. It is vital that all documents are kept as flat as possible during consultation. If a document has a tendency to roll, you can place archival weights at its edges to keep it flat. No marks of any kind should be made on any item.

- Do not lean, or place anything, on the material. This includes elbows, hands, laptops or anything else. The archival document should not come into contact with anything on the reading room table. Placing undue pressure on a rare book can severely damage its spine.

- Use the cotton/nitrile gloves provided when consulting photographs. Photographs must be held by the edges at all times. The TV programme ‘Who Do You Think You Are’ shows users wearing white gloves while consulting archival documents. However, in practice, users are not encouraged to wear gloves (unless consulting photographs which can be stained by fingerprints), as they are often fit poorly, leaving spare material at the top of each finger. This reduces dexterity and makes paper harder to handle, which often results in more harm to the document than good.

- Carefully consult outsize material. The term outsize (OS) is generally used to refer to material which is larger than A4 size, as it does not easily fit into a standard archival box. This material must be stored separately, either in specially-designed OS boxes, or in a map cabinet. This material, when brought to the reading room, must have a flat surface on which the entire of the document rests. The edges of the document must not hang over the edge of the table, and it must not be placed on top of the desk’s plug sockets, or the wires of a user’s laptop. As above, it is important that the user does not lean on the document during consultation. Users should also take great care to ensure that they do not ‘squash’ or fold its edges against the table while reaching across the table to view the other side of the document.

- Use book rests as appropriate. It is important, whether consulting an archival pamphlet or a rare binding, to support the item at all times. Book rests or pillows are designed to support the document, while the lead weights, sometimes called ‘snake weights’, are placed at the edges of the document or book to keep it flat or open. You must never use your hands to press a bound volume open.

click on each image to zoom

Remember…

While there are more ‘don’ts’ than ‘dos’ in the reading room rules, it is best to think of them as a set of positive steps you can take for the long-term preservation of original material. Once you’ve practiced handling fragile material a few times it will become second nature.

More importantly, once you’ve mastered these handling techniques, you can get on to the best part of consulting archives — the excitement of holding a document that’s hundreds of years old, or finding a source that will take your research project from good to amazing!

How do I cite archival material?

The Glucksman Library has several online LibGuides relating to the citation of printed material, for instance, Cite it Right (Harvard) and Endnote. However, users are often unsure how to cite unpublished archival material.

The key to archival citation is good note-taking

In order to ensure each archival record is both findable, as well as understandable within the context of its collection, archivists note a number of essential elements of information, or ‘metadata’, about the record during the cataloguing process. These elements are included for every item or file in every archival catalogue, and are are vital to note while consulting any archival record. These key elements of information ensure that you know exactly what source you consulted, especially if you are consulting several items at once. They will help the department staff to locate the item for you, if you wish to consult it again. Moreover, these key elements of information about an archival item form the basis for its citation.

- Reference number (assigned by the archivist, usually written on the top-right corner of the page)

- Title

- Date

- Name of the creator (who wrote the letter? what department published the report? what collection is the photograph part of?)

For more on the key information or metadata recorded in the archival catalogue, see How do I read an archival catalogue?

Irish guidance for citing original archival material

You must study the referencing style required by your faculty or publisher closely. The Department of History at the University of Limerick publishes an undergraduate handbook and postgraduate handbook each year, outlining the basic style of referencing students should use in their coursework. This referencing style, as well as the majority of other history departments and publications in Ireland, is based on the Rules for contributors to Irish Historical Studies, published by Irish historian TW Moody in 1944.

In addition to the essential elements of information outlined above, and like any printed work, the IHS referencing guide states that you should note the precise page number of the archive material where appropriate, for example for letters and reports, or the folio number of the manuscript.

The IHS guide also requires you to note the name of the archival repository where you consulted the material. For well-known repositories, such as the National Archives of Ireland or the National Library of Ireland, these can be shortened to NAI and NLI respectively. For less well-known repositories, the full name of the repository should be included in full.

See also the National Archives of Ireland (NAI) guide to referencing archives here.

5. Critical thinking and analysis

What insights do archival documents provide?

Archives provide evidence of past ways of living, and this can give us new insight or a different perspective on our lives today. This material is important, for more than just a study of history, as the collections are about people more generally. It’s important that we have an awareness of our heritage, about the decisions behind the laws that are made and how politics, religion and social structures affected people in their everyday lives. Moreover, in the era of ‘fake news’, archives teach us the importance of context, and the importance of critically analysing any material we’re faced with, to investigate who created the record and why, and what it means in its broader context. This cumulative storytelling throughout history tells us who we are, and where we’ve come from.

Archives teach students to be curious and cautious about what they read, to follow lines of inquiry that may not be immediately obvious, to critically assess what each document means, and what this tells us about a person, event or institution that we didn’t know before. The skills you use while you research, find, analyse and reflect on archival material are all highly transferrable to other areas of your study, as well as your future career.

How do I analyse archival documents?

The critical analysis and interpretation of archival documents should be undertaken on a case-by-case basis, depending on the type of record you’re working with. As a general rule, it is important that a researcher questions each aspect of the record’s content, format and context, and that they are careful not to make any assumptions about what they read without first interrogating the evidence. For more on interpreting and anlysing archival documents, using diaries as an example, click here. For a sample document analyses, click here.

Important questions to ask yourself include:

- Who wrote/produced the document? What do you think their motivation was? Who do you think their intended audience was?

- If the document is undated and the location of its creation is undisclosed, what clues do we have to point to this information?

- Is the author a reliable source? What bias(es) may they have? How can you tell? How does this item compare to other sources on the same topic?

- What possible bias(es) and interpretations exist in related secondary sources?

- Is the source reputable? What is the custodial history? Can it be accessed by others for verification, i.e. have you been granted exclusive access?

- Are there any ethical concerns in consulting and publishing the contents of this document? Does it contain any sensitive information? How should such information be presented so that it is respectful to the data subject?

- When analysing a digital image from the archive, has the image been altered in any way? How can you tell? Is it a true representation of the original?

- When analysing a handwritten or audio record, have the contents been transcribed? If so, is this transcription verbatim or edited? What quality controls were in place to guarantee this process? How do you know?

- Remember that the dangers of the loss of context are especially true when accessing material online. When looking at a digitised collection, or portion of a collection, are there any (un)intentional missing elements? What is the digitisation policy or strategy of the holding institution?

Where are the best places to look for background research?

In order to extract the largest amount of information from any archival source, any and all incidental references to third parties, locations, events and institutions mentioned should be followed up – these can easily be traced in records from around the same time, and allow us to find out even more about the creator(s) and their world. The following is an example of the types of sources that can be used in conjunction with other archival records, to triangulate evidence, check spelling and provide additional contextual information. For more on contextual and background research see section 3 above, How do I find other archival collections that are relevant to me? as well as related lesson on archival transcription and the archival research journey.

Samples of sources for contextual research:

- Census returns: even if not from the same year as a specific record, these records contain helpful records of people’s surnames, localities and occupations

- Unusual placenames may be recorded on Logainm

- Individual family estates or houses may appear on the Landed Estates Database

- English landowners or peers may be listed on The Peerage

- Birth, marriage and death certificates

- Land records, especially lists of estates and tenants

- Thom’s directories, street indices, etc.

- Google maps

- Newspapers

- Court records

- Published works

- Online biographies, such as the Peerage, the Cambridge Dictionary of Irish Biography and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- See also our A–Z list of online archival resources

6. Further reading and resources

General introduction: archives, the archivist and archival resources

- Watch the video introduction (20 mins) to the Special Collections and Archives Department at UL

- Watch archivist Dr Kirsten Mulrennan outline the work of an archivist and the department in her UL Talks video (5 mins)

- See our list of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) in relation to archives and archival research.

- For a list of useful resources relating to archives and archival research, please see our A–Z of online resources. This list is continuously updated.

- For a list of useful resources relating to historical research, please see our amalgamated reading list.

Introduction to archival theory and the history of the archive

- Verne Harris, ‘The Archival Sliver: Power, Memory and Archives in South Africa‘, Archival Science 2 (2002).

- Eric Ketelaar, ‘Tacit Narratives: The meaning of archives‘, Archival Science 1 (2001).

- Joan M Schwartz and Terry Cook, ‘Archives, records, and power: The making of modern memory‘, Archival Science 2 (2002).

- Alexandra Walsham, ‘The Social History of the Archive’, Past and Present 230 (2016).

- Queen’s University Archives, ‘About the Archives‘.[↩]

You must be logged in to post a comment.